"Letter to His Son" by Lord Chesterfield

"Talk often, but never long: in that case, if you do not please, at least you are sure not to tire your hearers. Tell stories very seldom, and absolutely never but where they are very apt and very short. Omit every circumstance that is not material, and beware of digressions. To have frequent recourse to narrative betrays a great want of imagination.

Never hold anybody by the button, or the hand, in order to be heard out; for if people are not willing to hear you, you had much better hold your tongue than them.

Avoid as much as you can, in mixed companies, argumentative conversations. But if the conversation grows warm and noisy, endeavor to put an end to it, by some genteel levity or joke.

Above all things, and upon all occasions, avoid speaking of yourself, if it be possible. Such is the natural pride and vanity of our hearts that it perpetually breaks out, even in people of the best parts.

Alway slook people in the face when you speak to them: not doing so is thought to imply conscious guilt; besides that you lose the advantage of observing by their countenances what impressions your discourse makes upon them. In order to know people's real sentiments, I trust much more to my eyes than to my ears: for they can say whatever they have a mind I should hear; but they can seldom help looking what they have no intention I should know.

Never give nor receive scandal willingly; for though the defamation of others may for the present gratify the malignity of the pride of our hearts, cool reflection will draw very disadvantageous conclusions from such a disposition; and in the case of scandal, as that of robbery, the receiver is always thought as bad as the thief.

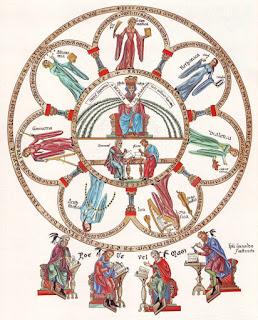

But to conclude this long letter: all the above mentioned rules, however carefully you may observe them, will lose half their effect if unaccompanied by kindness and the Graces. Whatever you say, if you say it with a supercilious, cynical face, or an embarrassed countenance, or a silly, disconcerted grin, will be ill received. If, into the bargain, you mutter it, or utter it, indistinctly and ungracefully, it will be still worse received. If your air and address are vulgar, awkward and gauche, you may be esteemed indeed, if you have great intrinsic merit; but you will never please; and without pleasing, you will rise but heavily. Venus, among the ancients, was synonymous with the Graces, who were always supposed to accompany her; and Horaces tells us that even Mercury, the God of Arts and Eloquence, would not do without the Graces."

Such a good reminder for me today! :) From EveryDay Graces, by Karen Santorum.

Comments

Post a Comment